Speedy Thing Goes In...

Portal is a first-person puzzle-platform game, released by Valve Software in 2007 as part of a product collection called the Orange Box, (Amazon, Steam) which included Half-Life 2, its sequels Episode One and Episode Two, and Team Fortress 2. Unlike its violent (if very smart) counterparts, Portal was a revolution in gaming.

In Portal, you play as Chell (gasp! a female protagonist! and a non-sexualized one!), navigating your way through a series of physics and logic-based tests. Your only weapons are your own mind and a portal device. On most surfaces in the game, the device can place two portals, which create a visual and physical connection between two locations in three dimensional space. A very important aspect of using the portal gun is the principal of redirected but conserved momentum: objects (or people, like Chell) maintain speed when traveling through the portals. This allows the player to access otherwise impossible areas. Check out one of the most challenging and rewarding levels, Test Chamber 18:

The revolutionary nature of Portal (and its 2011 sequel) goes beyond these aspects. Once I played the developer's commentary, I discovered a level of unsuspected profundity. First of all, the game design has a sophisticated grasp of teaching, especially the concept of the "zone of proximal development." In brief, this theory of cognitive development holds that people learn best when we give them tasks that are just a little beyond their mastery. When provided with appropriate models, people figure out how to complete the tasks on their own. And then there will be cake.

Beyond innovative game-play, Portal is great because of its (ostensible) antagonist: the rogue A.I., GlaDOS. Voiced by Ellen McLain, GlaDOS is a sinister and snarky presence, part guide, part personal trainer and all psychopath. It seems odd to state that this is really a large source of Portal's charm: GlaDOS is the player's clue that there is a subtext to the straight-forward problem-solving we're doing. She takes over the smirking role that many of us have when playing first-person shooters, sticking her tongue firmly in her cheek for us.

Portal PedagogyThe revolutionary nature of Portal (and its 2011 sequel) goes beyond these aspects. Once I played the developer's commentary, I discovered a level of unsuspected profundity. First of all, the game design has a sophisticated grasp of teaching, especially the concept of the "zone of proximal development." In brief, this theory of cognitive development holds that people learn best when we give them tasks that are just a little beyond their mastery. When provided with appropriate models, people figure out how to complete the tasks on their own. And then there will be cake.

Or not, in Portal, but the point is that this game is the essence of well-designed experiential learning. The first few levels are literally "this is how you play the game," but they never feel like a sit-down lecture. They are instead a series of discrete problems to solve, slowly increasing in complexity.

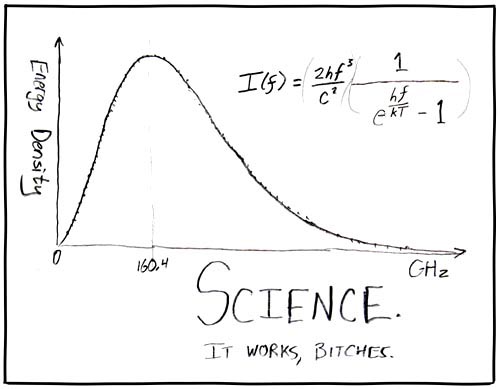

To boot, Valve's Source game engine recreates physics in a very realistic manner. So realistic, in fact, that educators are using Portal to teach about the physical properties of the universe, to interest children in things like math, science, logic, spatial reasoning, probability and problem-solving.

Portal Philosophy

Especially with Portal 2, the franchise goes beyond even those utilitarian domains. The addition of the character Cave Johnson allows the game to slyly lead the player towards an exploration of just what is science? The apocalyptic results of Aperture Science's experiments, it seems quite evident that science is not that they've been doing. But what I really appreciate about the game is that it doesn't hammer you with "This is how you define science, idiot!" Instead, it rewards your critical thinking. Because science is precisely how you win the game: observing, hypothesizing, testing and checking results. Think critically and creatively at the same time.

Portal Philosophy

Especially with Portal 2, the franchise goes beyond even those utilitarian domains. The addition of the character Cave Johnson allows the game to slyly lead the player towards an exploration of just what is science? The apocalyptic results of Aperture Science's experiments, it seems quite evident that science is not that they've been doing. But what I really appreciate about the game is that it doesn't hammer you with "This is how you define science, idiot!" Instead, it rewards your critical thinking. Because science is precisely how you win the game: observing, hypothesizing, testing and checking results. Think critically and creatively at the same time.

|

| http://xkcd.com/54/ |

Beyond an inductive exploration of the nature of science, the story and characters of both Portal and Portal II can lead us to all manner of investigations : about power (economic, technological, political), about history (what happened to the game world?), and even about feminism (a computer game where the female characters outnumber and consistently out-think the male ones is a rare gem, but that brings us back to ideas of power and the binary trap of patriarchy...)

...Speedy Thing Comes Out.

...Speedy Thing Comes Out.

This is really just a sketch of some of the issues that I want to explore more with Portal and Portal II. There are already quite a few folks out in the blogosphere that have ruminated on some of these things (especially GlaDOS) and over the next while I start talking about those ideas. I'm actually developing this for the Popular Culture Association and American Culture Associate national conference in April.

No comments:

Post a Comment